It’s time we started picking the right fights. The public debate is about controversy. What matters is, whose controversy.

Two years ago, saying that extreme weather was caused by global warming was a controversial position. So was saying that inflation was caused by corporate greed. Now, they are common opinions. This post below from two years ago reminds us that we have to pick arguments to set the agenda and reframe the debate!

Triggering the Conservatives

The only way to seize the agenda of the public debate is to say something that will trigger the debate you want to be having. If we can get over our fear of criticism, we can decide which questions will get the attention of the public and the press, just by using language that is, well, debatable.

“Global warming is causing life-threatening heat waves.” Let conservatives argue that it’s not. We win when the question being debated is whether or not these record heat waves are being caused by global warming.

“Record profits are evidence that companies are engaging in price gouging and crisis profiteering.” Let conservatives argue things like “it’s actually commodities markets that set gas prices.” We win when the question being debated is whether or not companies are taking advantage of the situation to drive up prices and rake in unprecedented profits.

It’s easy to find things to say that conservatives will object to. Conveniently for us, we have many beliefs that are true and that the majority of the public share, but are also “unspeakable” in the public debate.

It’s time to say things that we know are morally right and a little bit controversial.

Why do we avoid controversy?

I’ve been reading a lot of messaging memos lately. For the most part, they’re pretty good, or at least they’re headed in the right direction. The problem is that they don’t go far enough in the right direction. These memos, full of language that has been focus group tested, seem to have been scrubbed clean of anything that might get a reaction out of, well, anybody.

If you only say things that aren’t debatable, they won’t get any public attention-share in the debate. If you choose the language that offends the fewest people instead of the language that has the most impact on people, you will inevitably sound both weak and inauthentic.

This is how we started using terms like “everyday people.” Nobody in the real world talks about “everyday people.” There are everyday dinners and everyday clothes. Are there “special occasion people?” No, there are not. It’s okay to talk about “regular folks” or “the average person.” Somebody, somewhere may not like it, but at least you won’t sound phony and packaged.

Why do we do this? We seem to have developed a phobia about criticism. I know that we have been traumatized by decades of having every utterance leapt upon by conservatives, twisted to mean something different, and broadcast far and wide. Guess what? They’re only doing that to shut you up. To prevent the public from hearing what you have to say. And if you shut up, they have effectively gotten you to silence yourself.

Now, they are calling us socialists and “groomers” for absolutely no reason at all. We may as well express ourselves. What have we got to lose?

We’re always looking for the safest language to use, as though our goal in the debate were to appease those whose position is furthest from ours on the spectrum. We’re like that candidate who has shaken every hand in the room, but just can’t stop talking to that one guy who has yet to be won over by his or her charms.

Our job in the debate is to show that undecided person, that swing voter, that we are out there fighting for them. If we want people to believe we will fight for them, we have to pick some fights that help us make our point and show people that we won’t back down.

Thank you for reading Reframing America! This work is reader supported. To make sure you don’t miss a column, subscribe now to receive new posts by email!

All content is free, but some people choose to become paying subscribers to support this critical mission of improving our communication with American voters!

What is constructive controversy?

“The public debate” is not the same thing as “public opinion.”

You can actually get hammered in the media and win public opinion in the process. (Don’t worry, the press always comes around once they see where the public is.)

How did Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez change the public debate from one in which it was unacceptable to even mention the idea of raising taxes on anybody, let alone the rich, to one in which 85% of the American public agreed with her proposals to tax the wealthy? She did it by saying exactly what she believed and letting the entire press and business world pitch a fit.

After two weeks of standing her ground and making her case, the public was firmly on her side. Why? Because she forced this question into the public debate: “Are the extremely rich paying their fair share in taxes?” The American public thought about it and answered with a resounding, “NO.”

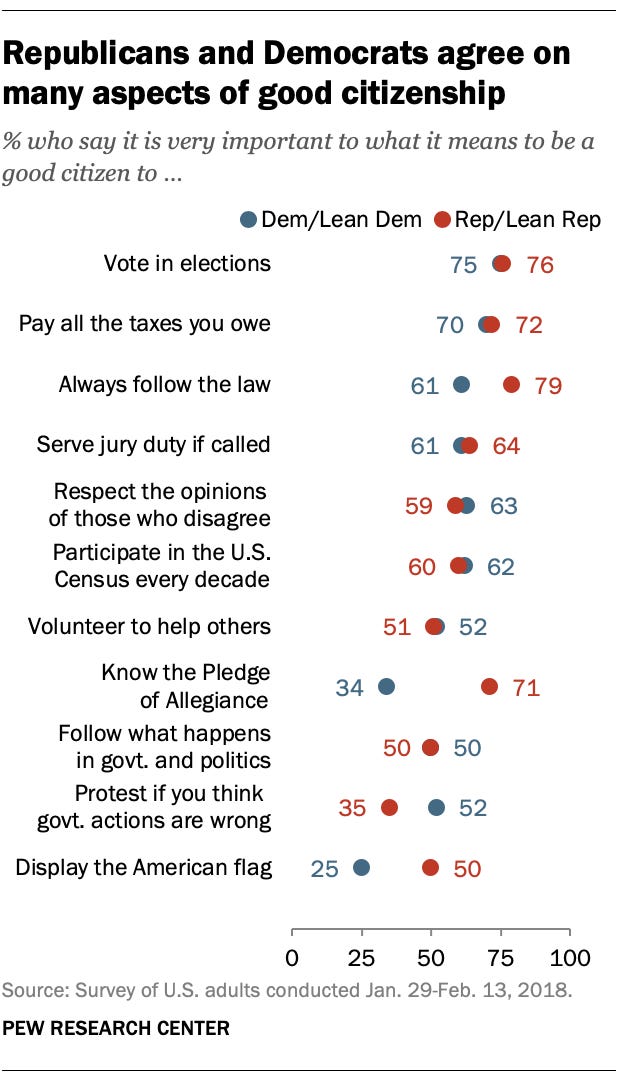

It is clearly a myth that talking about taxes will tank you in the polls. Opinion research shows that most Americans feel that paying taxes is a top patriotic duty. This opinion is also strongly bi-partisan.

This is a perfect example of the gap between “the public debate” and “public opinion.” For decades, the conventional wisdom has been that talking about raising taxes is suicidal for a politician’s career. Why? Because conservative pundits and anti-tax activists have been telling everybody that for decades, and we have been too afraid to challenge their myth.

The key to successful agenda setting is not backing down.

In the 2020 presidential primary debates, Lester Holt tried to “gotcha” the Democratic primary candidates by saying something like “raise your hand if you think we should eliminate private health insurance.” Elizabeth Warren did just that. When Holt asked her to explain her position she said:

“Look at the business model of an insurance company. It’s to bring in as many dollars as they can in premiums and to pay out as few dollars as possible for your health care. That leaves families with rising premiums, rising co-pays, and fighting with insurance companies to try to get the health care that their doctors say that they and their children need. ‘Medicare for all’ solves that problem.”

“And I understand. There are a lot of politicians who say, ‘oh, it’s just not possible, we just can’t do it, have a lot of political reasons for this.’ What they’re really telling you is they just won’t fight for it. Well, health care is a basic human right, and I will fight for basic human rights.”

Elizabeth Warren got an 11-point bump in the polls by hitting a gotcha question out of the park. She got people to ask themselves the question, “What purpose is private health insurance serving in this situation? Are they making a positive contribution that is worth the profit they take?” In my opinion, that’s exactly the right question that we, as a society, should be asking.

Rather than take the bait, conservatives pivoted to their classic “taxes are bad” stance and pushed her to admit she would raise taxes to pay for it. She could have said, “Right now people are paying obscene and escalating premiums and they still have to pay for the first $8000 of care. They would rather pay a smaller progressive tax with corporations picking up their fair share of the bill.”

Instead, she lost her support when she backed down to pressure and started watering down her support for Medicare for All. She should have stood her ground. After all, in mid-2019, Medicare for All had a 63% approval rate by the American public, even when you use the supposedly politically suicidal name “Medicare for All.”

If you want people to believe that you’ll stand up to Russia or China or mega-corporations, you had better show them that you can stand up to the press and conservatives. Say what you believe, and when conservatives attack, don’t back down. Use their opposition to keep the questions you want debated front and center in the debate.

How to Trigger the Conservatives

Here’s how this works:

First, figure out your perspective on the situation: what you want people to think.

Next, rephrase it in the form of a question: the question you want people to be debating. Try to form that question in a way that conservatives will object to and be unable to resist arguing about. If everybody agrees with you, it will drop out of the public eye and be replaced by something that people do disagree about. We need the argument to keep the story alive.

That’s how you set an agenda.

The extreme version of this is called “pulling a Tucker Carlson.” You “ask a question” in order to suggest something that you don’t actually want to take responsibility for claiming outright! Usually preceded by an un-sourced, “People are saying...”

Example (Hypothetical)

What do you want the American people to think?

Forcing people to remain pregnant is unconstitutional.

Rephrase that in the form of a provocative question.

“People say” that forcing people to remain pregnant constitutes “involuntary medical servitude.” Do bans on abortion violate the 13th Amendment ban on slavery?

Your mission is to get people to argue about these questions:

What does “involuntary servitude mean?

Is there such a thing as “medical servitude?”

Is forcing women to remain pregnant and go through labor for the benefit of another being or society as a whole, involuntary medical service?

We are on the “yes” side. We want to bait conservatives to jump in on the “no” side.

Conservatives can either agree with us (which they won’t) or argue with us, which puts them in the position of fighting against the constitution and for slavery. This is the tactic they use on us all the time. Either way, they give us a public platform to continue to make our case to the American people.

At the very least, we need to make strong positive statements about things we actually believe, especially those that are supported by the majority of the American people, and not backing down in the face of challenge by either the press or the conservative punditry.

The Bottom Line:

It’s time we started picking the right fights.

Agenda setting requires saying things in the public debate that are considered controversial, because the public debate is not about agreements, it’s about debates.

The key to setting the agenda is to determine which question you want want people arguing about, making a “controversial” assertion and then hoping somebody argues with you.

Our job isn’t to get treated nicely by the moderators or convince our opponents that they are wrong. It’s to communicate to the audience, the people observing the debate, where we stand: that we are on their side and willing to stand up to opposition on their behalf.

The parameters of what is “acceptable” in the public debate are far more conservative than actual public opinion. This gives us many opportunities to take “controversial” stands on issues where we actually have majority public support.

Thanks, as always, for reading. I hope you are able to use this in your work and your activism!

I look forward to your feedback and ideas.

Warmest Regards,

Antonia

As usual, this is great. I like to listen to The Bulwark (as an AOC progressive), and on a recent Podcast with Laura Barron-Lopez, from PBS Newshour, they touched on how good the GOP is at messaging: https://youtu.be/MWAU0dgiW0E?si=wkPeU-nrt30l54sj

and that were the shoe on the other foot, the GOP mediasphere would be 24/7 about Alito (and Clarence). I wonder how we should be framing and beating the horse incessantly on Alito and flags and godliness, and Clarence and bribes.

We want people to think that Alito and Thomas are political hacks posing as judges in the highest court in the land.

"People say that Alito is just a partisan hack posing as a SC judge. Does his flying the insurrectionist flags show he's biased toward conservatives and Christian nationalism?"

"People say that Thomas has been taking bribes for years. Does those millions in gifts from a conservative billionaire affect his rulings, especially in cases that involve his benefactor?"

Great points! But if we do as you say, which we should, we'd better know enough about the subject so we can be well-prepared to combat & refute arguments they may pose with hard evidence & sound reasoning. That is our challenge, and we should be up to it.