What’s the Point of Talking Points?

No, they’re not for talk shows. They’re for friends and neighbors.

Even if you are going on “Meet the Press,” the talking points you need aren’t the facts and figures people keep giving us. The purpose of a talking point is to give your supporters out there something they can say - in person - to friends, neighbors, and even total strangers. Word-of-mouth has always been the most powerful form of communication. Experts in consumer behavior tell us how it works and how to generate it.

Why Consumer Research?

For more than a hundred years, the business world has studied how advertising and marketing change thinking and motivate behavior. Their financial investment in behavioral psychology makes ours look like the change you find in the sofa. They know what works and what doesn’t because they measure the results in their bottom line. And, contrary to what some believe, things don’t “work differently” in politics.

Here is what the research tells us about who we are trying to reach, who they will listen to, what makes communication effective, and what role talking points play in the entire operation.

Thank you for reading Reframing America! This work is reader supported. To make sure you don’t miss a column, subscribe now to receive new posts by email!

All content is free, but some people choose to become paying subscribers to support this mission of helping everyone on the Left effectively communicate what we believe to American voters!

The Passively Informed

Who do we need to reach? Those who don’t seek out information.

We may find this hard to imagine, but some people don’t know a lot of the basic political facts we take for granted. We have to imagine it, because those people are our target audience.

In his new book, Reinventing Political Advertising, campaign legend Hal Malchow argues that advertising effects are greatest where people are the least informed. Malchow talks about an NEA/Analyst Institute study in which researchers divided the respondents into two categories based on their level of political knowledge.

Hal Malchow:

“In the New Mexico election experiment, voters who could not name which party controlled Congress were thirty-one times more likely to move in response to three mailings. Thirty-one times.”

“In a presidential race, we should be targeting voters who NEVER watch the news.”

People I call “information seekers” – regular consumers of news and political information – are least likely to be undecided. If we want to have the greatest impact possible with our political communication, we need to target people who don’t seek out political information, those who only get it when it crosses their path as they go about their day. Let’s call these people the “passively informed.”

So - how do you influence people who are not paying attention?

Small i influencers

The only people who can reach our target audience are their peers.

Who do you trust? If a Honda dealer told you that the Honda Accord is the best car on the road, would you believe them? Maybe. But what if your neighbor told you that they only buy Honda Accords because they have always been reliable? The Honda dealer probably knows a lot more about cars, but you trust your neighbor more. Why? Because your neighbor doesn’t have an ulterior motive. For the same reason, voters trust recommendations from ordinary people far more than they trust messaging from campaigns, the press, or even big I “Influencers” on social media.

Paul Lazarsfeld conducted a legendary study during the Presidential Election of 1940. His team closely followed the decision-making processes of 2,400 voters. They found that nine of every ten people made their decision based on the recommendation or information received from a friend or acquaintance. Only one in ten received their information directly from the media or the campaign. This is known as the “two-step flow” theory of communication.

The concept was popularized in the early 00s by best-selling books like The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference, by Malcolm Gladwell, and The Influentials: One American in Ten Tells the Other Nine How to Vote, Where to Eat, and What to Buy, by Edward Keller and Jonathan Berry.

This roughly nine-in-ten number has remained consistent through more than 80 years of additional research. According to Nielsen Research, in its global Trust in Advertising Study in 2021 which surveyed 40,000 people across 56 countries, 89% of consumers said that they trusted recommendations from people they know above all other forms of messaging.

Offline Word-of-Mouth

Advertising works by generating conversations in the real world.

92% of recommendations by a friend or peer happen offline, according to another Nielsen Research program, one that tracks the behavior of 30,000 people every year.

According to a comprehensive research project by the Wharton School of Business, the primary means by which broadcast advertising and social media work is by generating offline conversations.

In the study, advertising that did not generate word-of-mouth had virtually zero impact. Advertising that did generate word-of-mouth had an impact that lasted about two weeks. It is well known that the impact of broadcast advertising dissipates completely by two weeks after the ad is aired. This is why your TV ad vendors tell you to buy ads right before the election.

The only advertising that succeeds in impacting consumer behavior is that which generates word-of-mouth and keeps that word-of-mouth going.

The Purpose of Talking Points

Our supporters are not the target audience. They are the delivery method.

According to word-of-mouth marketing gurus Ed Keller and Brad Fay, authors of The Face-to-Face Book: Why Real Relationships Rule in a Digital Marketplace, the purpose of advertising and marketing communications is to reach people who are already your customers and give them the talking points to deliver to their friends and neighbors.

In our case, these are our supporters, not our consumers, but otherwise the process is the same. We give them the messaging we want them to deliver to our target audience through personal conversations in the real world. These conversations can be at the door, but they are best received in organic or non-political social settings.

Talking points must be verbally sharable, positive or informative, and properly framed.

Verbally Shareable

We have to make that message easy for them to deliver. That means, first of all, it must be written the way people normally speak.

Positive, Emotional and/or Useful and Informative

Jonah Berger, the head researcher on the Wharton studies mentioned above, is also the leading expert on what makes things go viral, as well as the best-selling author of Contagious: Why Things Catch On, and Invisible Influence: The Hidden Forces that Shape Behavior.

According to Berger, the messages that get shared, especially those that are shared in person, are not those that are the most biting or snarky, but those that are emotional, positive, and informative. Emotion motivates people to share, and people like to share things that make them feel good and helpful. That’s why the most shared types of content online are heartwarming animal videos, inspiring stories, and “Top five ways to do something.”

A snarky comment might make you feel good online when preaching to the converted, but when talking to people you barely know or don’t know, saying something negative about another person just makes you look like an a**hole. Attacks backfire more often than not, drawing sympathy to the object of your criticism, and causing supporters of your opponent to double down on their opposition.

Properly Framed

You can learn all about the importance of framing in my newsletter archives, but in my next few issues, I will elaborate on what makes talking points effective from the perspective of setting the agenda and framing the debate. It will have a lot to do with deciding which ideas and people we want to expose people to, what associations we want people to make, and how we communicate our values.

The Bottom Line

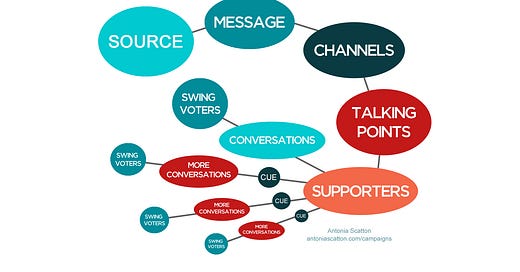

Here’s what the whole process looks like:

The campaign develops the message it wants delivered via word-of-mouth.

This message is intended for low-information voters.

Talking points are written to be verbally sharable.

They are positive and/or informative, so that sharing them makes supporters feel good about themselves.

They are framed to advance our strategic goals.

The campaign uses all available communication channels to deliver those talking points to supporters.

Supporters then deliver those talking points through in-person conversations with passively informed voters.

These word-of-mouth recommendations from “people just like them” succeed in influencing voter behavior where direct from the source communications fail.

THAT is how we use talking points to drive the word-of-mouth that actually delivers results.

Thanks, as always, for reading and subscribing! I hope you are able to use this in your work and your activism!

Stay warm and healthy!

Antonia

NOTES

Reinventing Political Advertising, by Hal Malchow

The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference, by Malcolm Gladwell

The Influentials: One American in Ten Tells the Other Nine How to Vote, Where to Eat, and What to Buy, by Edward Keller and Jonathan Berry

The Face-to-Face Book: Why Real Relationships Rule in a Digital Marketplace, by Ed Keller and Brad Fay

Contagious: Why Things Catch On, by Jonah Goldberg

Invisible Influence: The Hidden Forces that Shape Behavior, by Jonah Goldberg

What Drives Immediate and Ongoing Word of Mouth? Jonah Berger and Eric M. Schwartz (2011). Journal of Marketing Research

Very useful. Our group of Democrat's meet recently (40 of us) and I've decided to share it. Thank you.

Great newsletter, Antonia! Among the things that stood out to me:

“For more than a hundred years, the business world has studied how advertising and marketing change thinking and motivate behavior. Their financial investment in behavioral psychology makes ours look like the change you find in the sofa.”

One thing I never understand is how far political communication is from advertising techniques. It’s like nobody ever read a book about advertising. In 1968 people were shocked that the president was sold like a product; now I’m shocked that he isn’t.